The Future of the Design Studio and an Introduction to the ArchNet Project

An essay on a presentation made by William J. Mitchell to Diwan al-Mimar on February 25, 2000

Prepared by Mohammad al-Asad and Majd Musa, 2000

This essay deals with two interrelated subjects that William J. Mitchell (1), the Dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), presented to Diwan al-Mimar. The first subject is the future of the design studio. More specifically, he dealt with experiments that have been carried out over the past six years at MIT in the teaching of architectural design, and which have aimed at rethinking the idea and the tradition of the design studio. The second subject is the ArchNet project, an Internet-based on-line resource for architecture, urbanism, and related issues that MIT is developing with the support of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

William J. Mitchell began this presentation with a photograph of a design studio at MIT dating back to the late nineteenth century (figure 1). (2) What is intriguing about this photograph is that it depicts an environment that does not differ drastically from the design studio of today. The photograph shows the studio as an environment for working. In it one finds tools for creating representations of works of architecture, and also for carrying out mental processes relating to the exploration, analysis, and critique of these works of architecture. The traditional tools for carrying out these tasks include drafting boards, parallel slides, triangles, paper, and pens and pencils. These tools were used in the nineteenth century and are still in use today.

Figure 1: An MIT architectural design studio from the late nineteenth century.

The photograph indicates that the studio is also an environment that provides reference materials needed by the designer to support the design process. Such reference materials take many shapes and forms such as drawings pinned up on the wall, as well as shelves and filing cabinets containing books, magazines, and photographs. The more information one can place in the studio, the more effective it becomes as an environment for carrying out the design process.

Most importantly, the photograph shows the design studio as a social environment. In it, interaction structured around ideas related to architecture takes place. Such interaction includes various forms such as informal discussions among students, the more formal mechanism of the instructor critiquing an individual student's work, or what is known as the "desk crit", and the even more formal design jury.

Following that, Mitchell displayed a slide showing an MIT architectural design studio from about 1960 (figure 2). The slide indicates that the studio had not changed much over a period of around a century. The traditional tools for representation such as the drawing boards and the cardboard and wooden models are still in use. Also, the same traditional reference materials such as pinned up drawings, books, magazines, and photographs are a part of the studio space. Of course, the critique session indicates that the studio remains a setting in which the social function of interaction between students and instructors takes place.

Figure 2: An MIT architectural design studio from c. 1960 showing Louis Kahn (second from left) giving

a desk crit.

Mitchell sees numerous positive features of the functions of the traditional studio, and argues that they should be retained and accentuated. However, he also argues that some of the traditional physical and pedagogical aspects of the studio need to be reconsidered. To begin with, the traditional representations that designers make using their hands, such as drawings, and cardboard and wooden models, have their limitations in terms of expressing a certain design and the ideas behind it. Traditional drafting instruments are not as flexible as one requires them to be in creating representations of an architectural idea. Also, the designer's ability to analyze a design represented through traditional methods remains limited. (3) Consequently, more innovative and advanced representation tools need to be integrated into the design process.

Also, the information resources that designers need to support the design process, such as books, magazines, slides, and photographs, are not all readily available in the traditional studio space. Most of them are located in libraries, but would be more useful to the designer if located in the studio itself. However, realizing that goal using traditional methods of storing and providing information is not feasible.

The traditional studio is important because of the types of interaction that take place in it between the students themselves, between the students and their instructor(s), and between the students, instructors, and outside visitors. However, because of a variety of factors such as wide geographic distances and busy schedules, it is usually difficult to regularly invite the necessary specialists and participants in the design process from outside the studio, such as critics, consultants, and theoretical clients. This inability to foster regular and intensive interaction with these outside visitors is a limitation that negatively affects the functioning of the traditional studio.

Mitchell provides a number of suggestions that would allow us to overcome such limitations. In order to address limitations relating to representing architectural ideas, he suggests the incorporation of new computer-based representation and simulation tools, which would greatly expand the student's repertoire of representational capacities. As for limitations relating to the availability of reference materials, this can be dealt with through bringing the World Wide Web into the studio so that students would have direct access to the tremendous amounts of information available there. Finally, the limitations of interaction with outside visitors can be overcome through electronic remote connections. This would provide new opportunities for collaboration and for receiving advice and feedback. In the final result, such developments would lead to metaphorically breaking down the walls of the studio and connecting it to a much wider world beyond those walls.

The image taken recently of an architectural studio workspace at MIT illustrates the fundamental ideas behind what is being done at that institution to overcome the limitations imposed by the traditional studio (figure 3). The image shows that the traditional drawing board and drawing instruments are still in use, and so are traditional physical models. In fact, MIT faculty members encourage their students to continue using traditional methods of representation. However, we now see the addition of a computer terminal at the student's desk.

Figure 3: A late twentieth century student work space at an MIT architectural design studio showing traditional representation tools being used alongside the computer.

The computer provides access to CAD tools and other software that expand the range of representational capabilities for the student, and bring new tools to the design process. Moreover, the computer is connected to the World Wide Web. In this context, MIT is now working on scanning its slide collection and placing it online, and MIT Press is doing the same with a number of its books. Consequently, the computer that is located inside the studio becomes both a tool for creating architectural representations, and also a source for reference materials.

The computer in the studio can also become a tool for remote collaboration. This can take place synchronously, through video-conferencing technologies that enable the studio environment to communicate with remote critics and with students from other institutions. Also, collaboration can be established through asynchronous communications, by means of email and web pages. Here, students can post their work on a web site so that students, critics, and consultants in other locations can share their ideas with them.

This MIT "wired" studio space maintains all of the features of the traditional studio space, but also provide it with new capabilities. In fact, Mitchell emphasizes that his aim is to supplement the capacities of the traditional studio space rather than to substitute them. He adds, however, that other institutions take a different approach. At Columbia University, for example, considerable efforts have been made in recent years at developing the "paperless studio," where students do not use paper at all and carry their work in an exclusively electronic environment.

Mitchell does not advocate the paperless studio, and does not view it as the most productive approach for developing the design process. He believes that traditional design media and techniques remain valuable for many purposes. For example, he states that it is important for students to create models with their hands, which allows them to appreciate the importance of craftsmanship in the creation of high-quality architecture. He adds that freehand sketching remains an enormously important activity in the design process, and studies have shown that it is much more than a passive manner of depicting a preconceived idea in the mind of the designer. It is a technique that involves numerous cognitive cycles that significantly help the designer develop his or her design.

Also important is that the design process requires multiple representations of a given design. Mitchell's aim is to retain techniques inherited from the past, but to develop them using new technologies. He argues that students should be given the opportunity to learn about making choices from available representational tools - both traditional and new - and to translate back and forth between them as necessary.

The diagram shown in (figure 4) gives some insight into the relationships between the different traditional and new representational methods that may be used to execute the design task. Mitchell's vision is for the new design studio environment to be able to support the different modes of representation and the translation paths between them. Traditional representation methods include drawings, physical models, and the full-scale three-dimensional reality of the building itself. The new methods include digital models and various computer-aided design (CAD) / computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) systems.

Figure 4: Diagram showing translation paths between physical drawings, digital models, physical models, and the building itself.

With the introduction of CAD systems, designers have become more and more familiar with the process of translating back and forth between drawings and digital models. The process of printing or plotting takes the designer from the digital model to marks on the paper. On the other hand, the processes of digitizing or scanning take the designer in the opposite direction. What may not be so familiar yet is the translation process between digital models and physical ones. A designer can use three-dimensional digitizing and scanning techniques very effectively to transform a physical model into a digital one, and to carry out further work on it. Also, one can create a physical model out of a digital model. Here, designers can use three-dimensional printing and other prototyping techniques, which will be dealt with in more detail later in this essay. This allows them to send a CAD model to a three-dimensional printer to obtain a physical model.

Such developments are also having their effects on the construction process. There is an increasing use of technologies that depend on integrating CAD / CAM (computer aided-manufacturing) processes. Here, the production machinery can directly create physical components without the need to go through the intermediacy of traditional drawings. In other words, we can create a paperless construction process. Also, new techniques of electronic surveying and laser scanning can create digital models from the full-scale physical reality.

According to Mitchell, these various representational techniques and the relationships that are developing between them are important not only within the walls of academia, but are also becoming increasingly important in defining the new frontiers of architectural practice. Indeed, the process of creating Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao(1997; figure 5) was very much an example of the interrelated use of the technologies described above. The process began with creating traditional physical models. Using sophisticated three-dimensional digitizing techniques, these physical models were converted into digital ones. This involved the use of advanced CAD tools such as curved surface modeling systems. Prototyping technologies were used throughout the process to build back physical models from the digital models since Gehry is not comfortable relying solely on CAD visualization. The construction process also depended on CAD / CAM technologies, and a complete digital model of the building was used to drive fabrication machinery and onsite positioning machinery. All this made it possible to build this project within an acceptable budget and time frame. Also important is that this process, in both its design and construction phases, was completely globalized. The architect, client, site, and fabricators were in different locations, and were brought together by means of electronic telecommunications.

Figure 5: Computer simulated image of Frank O. Gehry's Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 1997.

Mitchell then proceeded to demonstrate the technologies that are being introduced into the design studio in order to take advantage of the capabilities of the electronic age. These include simulation technologies, prototyping and CAD / CAM technologies, remote collaboration capabilities, and the World Wide Web design environment.

Architects can make use of a wide variety of simulation technologies. One of these is photo-realistic simulations that address many subtle issues of importance to architecture. These issues include the effects of weathering and corrosion and the development of patinas on architectural surfaces. Consequently, such technologies allow the designer to explore the effects of weathering on a given design.

Designers can also benefit from digital collage capabilities that enable them to combine synthesized imagery with captured imagery (figure 6). This technique helps the designer explore architectural propositions in context. There are also a wide variety of non-visual simulations that look at issues such as the structural or thermal performance of a building, or the effects of wind flow on it.

Figure 6: Computer simulated image of Le Corbusier's Project for the Palace of the Soviets, Moscow, 1931.

Through the use of computer-generated animations, students can better explore the sequential experience of architecture. Faculty and students at MIT have been experimenting with rethinking the idea of the architectural section and looking at it as a dynamic experience rather than a static image. One idea that has been explored is to rotate the building through a section plane so that the designer can get a whole set of sections in sequence. Another has been to cut numerous parallel section slices through the building. Such techniques provide the student with new ways of understanding the relationships between space and structure, between spaces themselves, and between the interior and the exterior of a given architectural design.

Concerning the techniques of rapid prototyping and CAD / CAM technologies, Mitchell mentions a variety of techniques for producing physical models directly from digital models. Among these are computer controlled cutting devices that work on two-dimensional surfaces. These are very useful and are becoming very popular, both among students and practitioners. Another technique is three-dimensional printing using stereo-lithography. This technique involves firing laser beams under computer control into a tank of polymer resin. The volume of this resin that receives the laser gets solidified in the form of a physical model. Another technique is to use computer-controlled laser beams to cut and fuse resin-impregnated paper in order to get a physical model. Yet another computer-controlled technique is the three-dimensional deposition printer. It deposits tiny pellets of plastic under computer control to produce different three-dimensional forms.

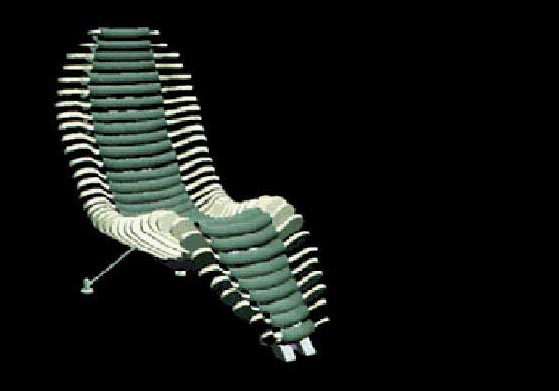

Mitchell provides an example in which these different computer-related techniques can be integrated into the design process. This consists of a recent three-week studio design project carried out at MIT, where small teams of students were asked to design and fabricate personalized chairs using a water jet cutter connected to CAD / CAM systems. The students were given total freedom in choosing the materials and creating the design they wished.

The students began the design process by collecting data about the sizes and shapes of the human body. In order to obtain such measurements, most of them made plastic casts. Using three-dimensional digitizers, they digitized the plastic cast, thus creating a CAD model. In order to develop their design concepts, some students started by freehand sketching while others developed their concepts using computer tools only. After completing the CAD models, a water jet cutter produced the real-scale chairs relying on CAD / CAM systems (figures 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). Mitchell views this example as representative of the new atmosphere of the MIT design studio, where the computer-cut pieces, freehand sketches, and computer printouts from CAD models all come together to create the final design. Such a combination of representational methods and tools definitely work to enhance the student's design experience.

Figure 7: Plastic cast made from a human model for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 8: Freehand sketches made for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 9: CAD model of a design carried out for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 10: Students asssembling pieces cut by a CAD / CAM operated water jet cutter for the chair

design studio project at MIT.

Figure 11: Full-scale model of chair designed and fabricated through the aid of CAD / CAM

systems for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Concerning the subject of remote collaboration in the studio, Mitchell shows how synchronous and asynchronous telecommunications can be used to establish remote connections with clients, consultants, manufacturers, critics, students in different institutions, and jurors. One example is a screen with one window where a student can have remote access to the CAD database and can sketch over the top of it, and another window where he has an audio and video connection with remote design collaborators (figure 12). This sort of setup is very much a kind of virtual conference table.

Figure 12: A computer screen image used by an MIT architecture student. The screen displays links to CAD and spreadsheet databases, and a video connection to a remote design collaborator.

Mitchell also shows how such technology can affect the structure of the jury. He shows the example of a student presenting his physical model and computer printouts to a traditional jury, with an additional jury member joining the process through telecommunication technologies (figure 13). Such technologies allow him to view and participate in the jury, and allows those in the studio in which the jury is taking place to see the remote juror and to communicate with him.

Figure 13: An MIT architectural design jury in which a remote juror (shown on the television screen) is participating through the aid of teleconferencing technologies.

Finally, Mitchell ends with what he refers to as the Web design environment. This can be thought of as a kind of integrating mechanism for pulling a number of the previous ideas together and making them available on a wide scale. Consequently, it is necessary to be able to integrate the World Wide Web with CAD and digital imaging so that designers can easily handle graphic and spatial materials that are useful to them. It is also important to be able to provide access to sophisticated tools that can only be found at distant locations from the designer. Therefore, providing remote access to digital libraries is of fundamental importance. Designers want and need to have the required information resources in the same environment where they are carrying out their design task. It is also important to provide personal and group workspaces and tools to support remote collaboration. It is such an environment that the ArchNet project, which he addressed next, aims at providing.

Questions and Answers:

The questions that were raised following the discussion addressed a number of themes. One of these themes dealt with how the quantity of work accomplished in the design studio will be transformed as a result of the introduction of new information technologies. Mitchell's response was that incorporating new tools related to information technologies in an extensive manner seems to lead to increasing the intensity of the experience of the student in the design studio. A larger quantity of work seems to be carried out in such studios in a given amount of time than is the case with traditional studios. If fact, it is difficult, if not impossible, to carry out the amount of work that can be achieved in an "electronic" or "digital" studio in studios where students rely exclusively on traditional design and presentation tools.

In this context, Mitchell cited interesting developments relating to experiments in studios that are involved in remote collaboration and are separated by significant time zones. He gave the example of a project where students at MIT collaborated on a studio project with students in Japan. A time difference of twelve hours separated the students in Japan from those in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The students very quickly figured out that they could use the time difference to get a twenty-four hour design process implemented. The MIT students would work for twelve hours and hand over the work to students in Japan, who would work for another twelve hours, hand the work back to the MIT students and so on. Of course, the students left an allowance for some overlap in the schedules so that they could synchronize and coordinate their activities. In the final result, the project developed at a much faster rate than it would have in a traditional studio.

However, Mitchell added that it remains unclear as to what the final shape of the digital studio will be. What is of importance is to have a flexible attitude concerning the development of the studio in the electronic age.

Another theme that the questions dealt with is the kind of skills that students need to acquire when dealing with such new technologies. Here, Mitchell emphasized that working with the computer related technologies he mentioned remains a form of craftsmanship. In that sense, it is not different from drafting or building architectural models by hand. It is therefore important that students are trained to appreciate the craftsmanship involved in dealing with such technologies. This is in spite of the fact that the separation of the human hand from the final product through CAD / CAM systems may initially lead one to think that the issue of craftsmanship becomes irrelevant when using new computer technologies.

In this context, Mitchell was also asked about the time frame needed to train students to deal with those technologies, and whether such training may require additional course work in relation to working within the context of traditional studios. His answer concentrated on the fact that more and more students today come to college with considerable skills in dealing with computers. They therefore often already have a considerable amount of the knowledge they might need in the electronic design studio.

Concerns were raised about the potentially negative impact that the introduction of new technologies might have on the quality of social interaction in the studio. Such technologies might tempt students to spend more time in cyberspace rather than communicating with their fellow students who share the same architectural space with them. Mitchell pointed out that these fears are exaggerated. In responding to this matter, Mitchell also concentrated on how we have to keep in mind that new communities are created in cyberspace, and that new forms of social interaction will develop between those who are connected online. He added that the electronic environment is an equivalent to a given architectural environment, and therefore it is important to design it properly so as to foster desired forms of social relations.

Another theme that was raised dealt the quality of the human-computer interface that characterizes computers today, which are often complex and far from being user friendly. Here, Mitchell agreed that the available interfaces are not as easy as one wishes them to be. This is in contrast to an example such as the cellular telephone, which contains electronic devices that are as sophisticated as those found in a computer, but is much easier to use than a computer. Mitchell adds that drawing with a mouse is almost like drawing with a rock in one's hand. He also cited the difficulties that were encountered at the beginning of the presentation in connecting his laptop computer to the LCD screen projector as an example of the unnecessary difficulties we still have to continuously face when dealing with computer hardware. In the case of architecture at least, part of the solution to these problems is to think of developing computer hardware and software that provide continuation with traditional tools, rather than attempt to fully replace them.

In this context, he criticized examples that aim at designing works of architecture that are fully dependent on new technologies. Some of these examples go as far as trying to use computer programs to replace the human being in the design process. Mitchell indicated that most of these experiments have shown shallow results that do not express the depth and variety of the design process.

Finally, questions were raised concerning how relatively resource poor institutions in a country such as Jordan can secure the necessary funds to obtain and upgrade the needed hardware and software that would connect them to the new technological developments currently affecting the field of architecture. Mitchell mentioned that there is no easy answer to this challenge. He emphasized that resource poor institutions should at least concentrate on obtaining and upgrading a minimal quantity of the latest available hardware and software that would allow its faculty and students to remain abreast of developments taking place globally. He also emphasized the need for resourcefulness on behalf of the administration of such institutions. For example, academic institutions often can obtain hardware and software from producers and distributors in the market for free, or at least at highly reduced prices. He also cited examples taking place in India, where some institutions have experimented with allowing outside entrepreneurs to establish computer labs on their grounds that function on a commercial basis, in the same manner as Internet cafes. Although such labs will charge the students for the use of their facilities, they will need to offer reasonable prices to attract the students as their customers.

The ArchNet project:

Following the presentation on the future of the design studio, William J. Mitchell introduced the ArchNet project. Mitchell defined ArchNet as an Internet-based network that provides both a resource and an on-line community for students, scholars, and design and planning professionals, worldwide, but especially in the developing and the Islamic worlds. The fundamental objectives of this project are to promote intercommunication among members of the architectural community throughout the world and to facilitate the sharing of resources between them.

The audience for ArchNet is a widely conceived one. It includes architects, planners, designers, and historians who function in a variety of capacities including students, scholars, educators, and practitioners. The range of topics that ArchNet addresses is also broad. It is intended to support both design work and scholarship. This broad scope will be represented in the ArchNet digital library, which will address issues including historical and contemporary architecture, urban design, building technologies, development and planning, landscape architecture, and restoration and conservation.

A preliminary ArchNet Internet site was launched in September 1999, but many of the capabilities of ArchNet will not be ready and available to the public until September 2000, and it will be yet another year from then before the project is fully operational. The project is centered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) School of Architecture and Planning and is being sponsored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Collaborators for the project include the MIT Press, as well as the Graduate School of Design and the Fogg Museum at Harvard University. A group of seven partner institutions consisting of universities and research centers located throughout the developing world are also participating in the project. The partner institutions will have access to the technical expertise of the ArchNet team. More importantly, however, they will participate in shaping the evolution of the project and in defining its goals and priorities, and will get the opportunity to present local architectural traditions and the work of local architects and scholars to an international audience.

Mitchell emphasized that ArchNet is much more than a site on the world-wide web. It is built around a large-scale digital library, but access to the system is through individual personalized workspaces available to all participants. It is very much a community-oriented site in that every member has a place in the system. ArchNet also provides a very strong support base for geographically distributing collaborative work. In fact, it is intended to support an international community of interest, and not simply to function as an electronic distribution mechanism. Consequently, ArchNet emphasizes community formation and community maintenance. Furthermore, it is being built on established institutional structures and human networks, and is institutionally grounded in a manner that makes it sustainable in the long run.

Anyone can enter ArchNet www.archnet.org to register and become a member. Members will have access to their own individual workspaces that enable them to present themselves to the rest of the ArchNet community through a variety of means including (but not limited to) their portfolios, curriculum vitas, or writings. ArchNet also includes group workspaces, job listings, discussion groups, course syllabi, profiles of members, a continuously updated digital calendar, and a sizable digital library.

ArchNet members can get into group workspaces to carry out collaborative projects. They can allow other members to get into their own pinup spaces to observe the latest sketches that they have posted, to comment on them, and to engage in a discussion of them. Members of ArchNet can also access the digital calendar and look at events that have been listed there. They can add an event, thus making it immediately available on a worldwide basis to all members of the ArchNet community. Members can go to the digital library and explore a variety of databases, such as that consisting of projects awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Consequently, Mitchell emphasized the idea of ArchNet as one that makes a wide range of electronic capabilities developed at a place such as MIT available to a much wider international audience. This is carried out in a framework that allows for a tremendous and effective sharing of resources, in a spirit of division of labor. Such a process maximizes the effectiveness of the efforts of all involved. For example, schools of architecture have generally similar slide collections that are maintained at great expense. Through a project such as ArchNet, each institution would concentrate on building a slide collection in the fields in which it has considerable expertise, and would contribute the results, in digital form, to all members of the ArchNet community. In return, that institution would gain access to the specialized slide collections of the other members of the ArchNet community.

Questions and answers:

One of the questions that were raised regarding ArchNet was whether institutions have priority in registering in ArchNet over individuals. Mitchell emphasized that ArchNet is not limited to institutions, and that individuals, rather than institutions, are the fundamental unit of ArchNet. In this context he made an analogy to the process of getting an answer from a computer system. One option is to have the system's search engine look up for the answer. A more effective and interesting manner, however, would be for the computer to point out to a person who knows the answer. Consequently, ArchNet emphasizes the idea of community orientation through allowing each person to set up his or her own personal space in the system. Consequently, each member would present himself or herself in whichever manner they prefer, through their designs, writings, areas of interest, ... etc. Through this mechanism, each member would be able to find and contact other members who may have answers or may have an interesting perspective concerning a specific issue.

Considering the shortage of resources that students, scholars, and professionals face in a developing-world country such as Jordan, members of the audience expressed an interest in knowing more about the digital library that ArchNet is developing. Mitchell mentioned that the digital library includes text, images, computer-aided design (CAD) data, CAD models, ... etc. The library will initially include the huge amount of material that has been collected and developed for over a period of over twenty years through the activities of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard and MIT. For example, through these activities about 500,000 slides have been collected, and almost all of them will eventually be available in digital form on ArchNet.

Mitchell added that another, and potentially more exciting, aspect of the digital library is that participating institutions will use ArchNet to make available to the broader ArchNet community materials that they have developed. Almost every school of architecture in the Islamic world has accumulated considerable documentary collections on local architectural traditions in the form of photographs, slides, and drawings. One of the aims of ArchNet is to digitize such information and make it available, on-line, to the members of ArchNet. Mitchell added that the contents of such a digital library would continue to grow in directions determined by the needs and interests of the members of the ArchNet community.

Notes

(1) William J. Mitchell is Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences, and Dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at MIT. He also serves as Architectural Adviser to the President of MIT.

His publications include:

E-Topia: Urban Life, Jim --But Not As We Know It (MIT Press, 1999)

High Technology and Low-Income Communities, with Donald A. Schon and Bish Sanyal (MIT Press, 1999)

City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn (MIT Press, 1995)

The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (MIT Press, 1992)

Digital Design Media: A Handbook for Architects and Design Professionals, with Malcolm McCullough (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991)

The Electronic Design Studio: Architectural Knowledge and Media in the Computer Era (edited with Malcolm McCullogh and Patrick Purcell (MIT Press, 1990)

The Logic of Architecture: Design, Computation, and Cognition(MIT Press, 1990)

The Poetics of Gardens, with Charles W. Moore and William Turnbull Jr. (MIT Press, 1988)

Computer-Aided Architectural Design (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977)

Before coming to MIT, he was the G. Ware and Edythe M. Travelstead Professor of Architecture and Director of the Master in Design Studies Program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He previously served as Head of the Architecture / Urban Design Program at UCLA's Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, and he has also taught at Yale, Carnegie-Mellon, and Cambridge Universities. In the spring semester of 1999 he was visiting the University of Virginia as Thomas Jefferson Professor

He studied at the University of Melbourne, Yale University, and Cambridge. He is a Fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a recipient of honorary doctorates from the University of Melbourne and the New Jersey Institute of Technology. In 1997 he was awarded the annual Appreciation Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan for his "achievements in the development of architectural design theory in the information age as well as worldwide promotion of CAD education."

(2) MIT, which started offering courses in architecture as far back as the 1860s, has the oldest department of architecture in the United States.

(3) For example, a set of drawings, no matter how extensive it is, cannot provide totally comprehensive information about the design it represents. Although physical models provide information that drawings cannot provide, especially concerning the three-dimensional qualities of the forms and spaces of a given design, they also have their limitations. For example, they do not give adequate information on matters such as the relationship between the interior spaces of a given design or the relationship between its interior and exterior spaces.

List of illustrations:

Figure 1: An MIT architectural design studio from the late nineteenth century.

Figure 2: An MIT architectural design studio from c. 1960 showing Louis Kahn (second from left) giving a desk crit.

Figure 3: A late twentieth century student work space at an MIT architectural design studio showing traditional representation tools being used alongside the computer.

Figure 4: Diagram showing translation paths between physical drawings, digital models, physical models, and the building itself.

Figure 5: Computer simulated image of Frank O. Gehry's Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 1997.

Figure 6: Computer simulated image of Le Corbusier's project for the Palace of the Soviets, Moscow, 1931.

Figure 7: Plastic cast made from a human model for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 8: Freehand sketches made for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 9: CAD model of a design carried out for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 10: Students assembling pieces cut by a CAD / CAM operated water jet cutter for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 11: Full-scale model of chair designed and fabricated through the aid of CAD / CAM systems for the chair design studio project at MIT.

Figure 12: A computer screen image used by an MIT architecture student. The screen displays links to CAD and spreadsheet databases, and a video connection to a remote design collaborator.

Figure 13: An MIT architectural design jury in which a remote juror (shown on the television screen) is participating through the aid of teleconferencing technologies.

Additional readings and useful web sites:

Al-Asad, Mohammad. "Message from Amman: The Future of the Design Studio" Mimarlik Culturu Dergisi XXI 2 (May - June 2000), forthcoming.

Giovannini, Joseph. "Computer Worship." Architecture (October 1999): 88 - 99.

http://www.arch.columbia.edu/DDL

This site is for the Digital Design Laboratory of the Graduate School of Architecture and Planning in Columbia University in New York. It provides connections to papers and reports on the subject of computing in architecture. It also provides information about the paperless design studio and exhibits architectural work carried out using the computer technologies.

http://www.ecaade.org/

This site is for the Organization of Education in Computer-Aided Architectural Design in Europe (ECAADE). The site provides connections to numerous papers on computer-aided architectural design especially those related to ECAADE's annual conference.

http://www.guggenheim-bilbao.es/ingles/edificio/el_edificio.htm

This site is for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. It provides information on the design of this building.

We welcome your comments and questions concerning this essay and will make all efforts to publish them on this site. Comments and questions may be edited for purposes of clarity and space.postmaster@csbe.org.