Rehabilitating Old Aleppo

Urban Crossroads #39

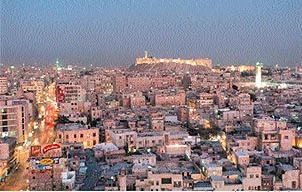

General view of Aleppo with the Citadel in the background. (Paul Halin)

The Graduate School of Design at Harvard University recently awarded its 2005 Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design. The prize, which was established in 1986 on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the founding of the university, is given once every two years. Its recipients have included well-known architects such as Norman Foster of the United Kingdom, Fumihiko Maki of Japan, and Alvaro Siza of Portugal. The award also has been given to two cities, Barcelona and Mexico City. This year, the recipient of the award is the city of Aleppo, more specifically, the rehabilitation project of the old city, which is being carried out by the Municipality of Aleppo in cooperation with GTZ (the German Agency for Technical Cooperation).

Aleppo is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities of the world. Over the centuries, it evolved as a highly cosmopolitan multicultural center of trade and industry. Its urban fabric reveals layers of habitation belonging to the Greek, Roman, Persian, as well as Muslim periods. The old city as it survives today is primarily the result of developments that took place since the twelfth century under Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman rule. Thousands of historical structures literally have come down to us in old Aleppo, the best known of which is its majestic citadel.

As with other historical cities in our region, old Aleppo has suffered greatly during the modern period. Its scenario of decline is not unique. Since the late nineteenth century, and especially after the middle of the twentieth century, the more affluent inhabitants of the old city gradually began to move out to modern residences built at the outskirts of Aleppo. In their place, lower-income groups, primarily rural populations migrating from the countryside, moved in. Most often, individual houses were divided up amongst a number of migrant families. Other houses were rented out as sweatshops or storage facilities, and some even were left to decay. The businesses of the old city also moved to the new districts of Aleppo, thus depriving the old city of much of its economic base. The historical architecture of the old city consequently has suffered from a combination of abuse and neglect, and the traditional vibrant socio-economic composition of old Aleppo has been greatly undermined. Its population declined by about a third over the past three decades so that today only 5% of Aleppo's almost two million inhabitants reside in the old city.

Another destructive force of the modern period to have affected old Aleppo is the usual culprit, the automobile. Beginning in the 1950s, wide streets that accommodate vehicular thru-traffic were built in the old city. As a result, parts of the old city's delicate traditional fabric, which consisted of narrow bending streets, a good number of which were cul-de-sacs, were ruthlessly destroyed. The new streets cut through neighborhoods, and separated and isolated them from each other, thus damaging their social and physical cohesiveness. They also brought thru-traffic from other parts of the city, and with that came high levels of noise, air pollution, and traffic congestion.

A number of positive developments later began to take place. The cutting of thoroughfares was halted in the late-1970s. In 1984, UNESCO declared the old city as a World Heritage Site, and in 1992, the Municipality of Aleppo and GTZ initiated a program for the rehabilitation of the old city.

The rehabilitation project has emphasized a number of issues. One is preserving not only the important monuments of the city, but also its traditional residential structures. The houses of old Aleppo have suffered greatly from poor maintenance, and since their new inhabitants primarily belong to lower-income groups, they have not had the financial ability to restore their houses. The project consequently initiated a program that offers small, interest-free loans along with free technical support to allow the inhabitants to carry out restoration work on their houses. This initiative has been successful, and hundreds of homes so far have benefited from these loans.

The project also has emphasized developing the old city as one that embraces a balanced set of mixed uses, a prerequisite for the well-being of any urban center. This means developing the legal and economic environments that encourage residential, commercial, cultural, and administrative uses to co-exist in the city. It also means that uses that bring excessive amounts of traffic, pollution, or noise would need to be zoned away from these mixed-use areas. Amongst other things, the project therefore has targeted the parts of the old city that had declined into sweatshop or warehouse districts, and has worked on upgrading them to accommodate healthier city functions. As the project aims at achieving a mixed-use balance in the old city, an emphasis - if not a priority - is given to residential use, which remains the backbone of any healthy mixed-use setting.

Within this context, it is interesting to note that an increasing number of houses in old Aleppo are being converted into restaurants and small hotels. On one level, this is viewed as a positive development since it is a sign of an increasing appreciation of old Aleppo and its physical heritage. These new establishments also bring considerable additional economic activity to the old city. The project personnel however also are aware that the spread of such establishments should be kept within reasonable limits. An overabundance of hotels and restaurants might overwhelm the residential character of the old city, thus converting it into an artificial museum setting. More importantly, an uncontrolled spread of these hotels and restaurants will bring in levels of traffic that the old city eventually will not be able to handle. In addition, hotels and restaurants can cause intense amount of noise, especially when banquets, parties, and weddings take place in them, thus making life intolerable for surrounding residents. The project therefore aims at keeping the numbers of these converted restaurants and hotels at bay and subjugating them to specific performance requirements relating to issues such as noise and parking. There is an awareness that if these hotels and restaurants are allowed to take over old Aleppo, one would end up "killing the goose that lays the golden eggs."

A major challenge for the old city is traffic. Although the opening of thoroughfares in old Aleppo that took place during the 1950s and 1960s was halted in the late 1970s, the damage caused by them, including increased traffic congestion, continues to be felt. In dealing with these problems, thru-traffic that cuts through the old city is being discouraged through various mechanisms including an extensive use of one-way roads. Time zoning, which restricts certain activities such as deliveries to only specific times of the day, also is being used to address traffic congestion. In addition, parking is being prohibited in certain locations. In areas where parking is allowed, a differentiation is being made between parking for residents and visitors. In locating areas where parking is permitted, and in order to ensure ease of access, an important consideration is that people would not have to walk more than 500 meters from their parked car to their point of destination. The project also is exploring converting certain arteries into pedestrian zones at certain times, and encouraging the use of public transportation for movement inside the old city as well as to it and from it.

The challenges facing the old city of Aleppo are enormous. This rehabilitation project nonetheless expresses a deep awareness of these challenges and a will to face them. The project looks at the old city in a holistic manner that brings in physical interventions along with socio-economic development activities, and establishes the old city as a sustainable mixed-use setting for residential, commercial, touristic, and cultural activities. We in Jordan should closely examine this important project as we develop various urban heritage sites in the country into tourist destinations. Whether these sites are Jabal Amman and Jabal al-Luwaybdah in the capital, the historical parts of the cities of Salt and Karak, or towns such as Umm Qays, we can benefit a great deal from studying the challenges facing the old Aleppo rehabilitation project as well as the opportunities it has generated.

Mohammad al-Asad

May 5, 2005